UUP Working Group on CTEs Presented by Professor Tom Pasquarello Political Science Department

Click here for slides from the presentation presented on 3/11/2020

Date posted: March 12, 2020

UUP Working Group on CTEs Presented by Professor Tom Pasquarello Political Science Department

Click here for slides from the presentation presented on 3/11/2020

Date posted: March 4, 2020

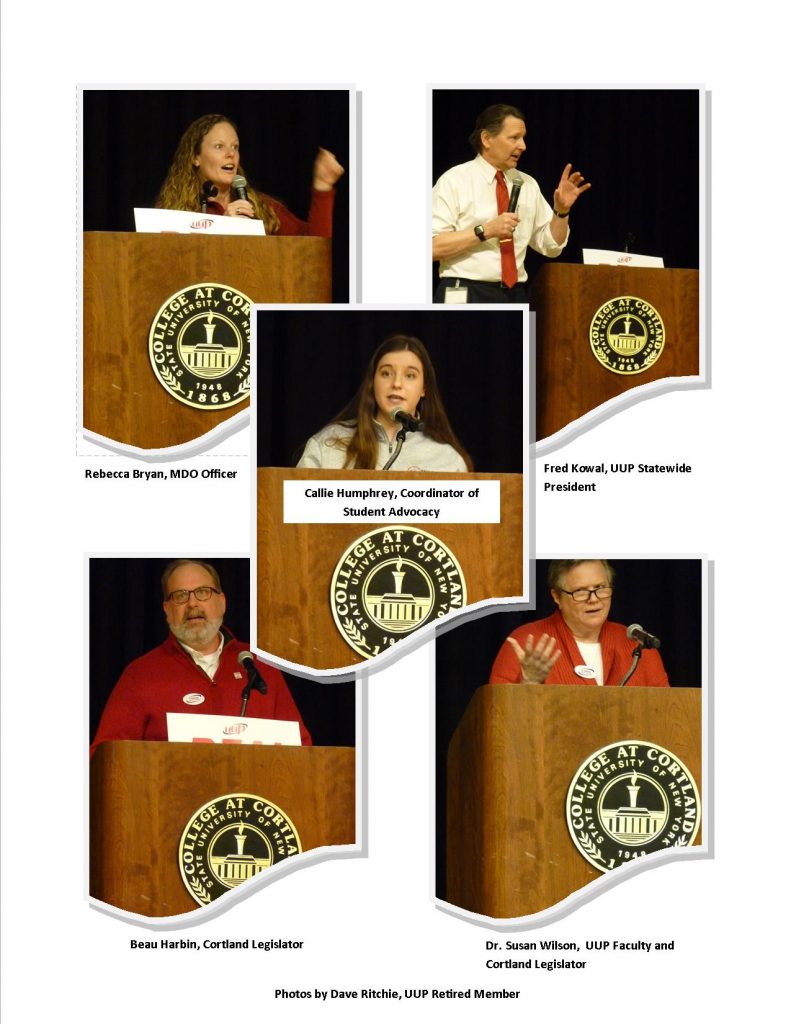

Fred Kowal, UUP Statewide President above, led the crowd in a chant of “Fund SUNY now!” that echoed through the Function Room in SUNY Cortland’s Corey Union. He told advocates that the only way to get more state funding for SUNY is to tell their elected officials to make it a priority.

Above, a group of Cortland Chapter advocates hold signs to amplify the importance of UUP’s push for more state funding for SUNY.

He also pushed for millionaires and billionaires in New York to pay their fair share through an enhanced Millionaires’ Tax and a pied-a-terre tax.

“I mean, c’mon, if you’re a millionaire and there’s a little increase in your tax rate, it will probably leave you as a millionaire,” Kowal said.

“We certainly cannot continue to allow the Legislature to underfund SUNY,” said Callie Humphrey, coordinator of student advocacy for SUNY Cortland’s Student Government Association. “A public higher education isn’t a privilege, it’s a right.”

Speakers included UUP Cortland Chapter President Jaclyn Pittsley; statewide Executive Board member and Cortland Chapter member Rebecca Bryan; and Cortland County legislators Susan Wilson and Beau Harbin.

Video taken by the Cortland Voice of the Rally: https://cortlandvoice.com/2020/03/05/uup-cortland-members-rally-demand-more-state-aid-for-suny-video-included/

Date posted: March 3, 2020

by Nancy Kane, PhD, Kinesiology Department –

Cries of “Huzzah!” ring out from students on the sidelines watching classmates practice skills used in medieval European jousting. Some students are acting as knights, some as squires or heralds, some as royalty. Four of them are getting a good workout as horses carrying the knights. One serves as scorekeeper. Shields have been emblazoned by competing teams, and the knights wear helmets designating them as belonging to the Gold or Silver team. It’s the day of the EXS 197 Joust, in which students in the History and Philosophy of Physical Education and Sport class experience some of the training used by knights in training.

The event was created by Dr. Nancy Kane (’13), who wanted to bring history to life after researching the training methods used in medieval times for her new textbook, History and Philosophy of Physical Education and Sport (Cognella, 2020). The book includes research and kinesthetic activities for each chapter to give students an engaging way to connect with the past and deepen their understanding. Kane was assisted in her research by Jeremy Pekarek, Archivist and Instructional Services Librarian at the Memorial Library Delta Collection, who made SUNY Cortland’s 1898 edition of Joseph Strutt’s book, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England (1801) available for her study. “I could have read it online, but there is nothing like holding the book, feeling its textures, and studying the words and engravings up close,” says Kane, whose students previously met with Pekarek to learn about Cortland’s archives.

The skills for the students’ jousting day include tilting with jousting lances (made of pillow-topped salvaged bamboo sticks) to spear rings, hitting a target (or a squire), and eventually competing in single combat against another opponent on “horseback.” The various events are described in Strutt’s book as practicing against a quintain, which could mean any of a range of targets from posts to squires holding shields. Quintains could also be rings used as targets: Strutt notes that the French scholar, Charles du Fresne, sierur du Cange (1610-1688), indicated that the Florentines in Italy referred to tilting at rings as “correr alla quintana.” Strutt also credits ancient Roman military training as noted by Vegetius in his book, De re militari., in which knights and squires would use a tree trunk to practice ad palum (against the pole). Eventually, shields and other targets were added, and tilting for rings remained a popular pastime among youth for centuries after the last tournaments faded from memory.

Kane used Strutt’s first chapter in Book III with its illustrations to recreate the training techniques and adapt them for a modern classroom. Strutt’s quintain illustrations were taken from an early 14th century manuscript in the Royal Library, Les Etablissmentz des Chevalierie, which were studied by the engraver and historian Strutt. “Many of my students are physical education majors, and I want them to experience some ways in which we can make history live and they can integrate history into their future classes to bring extra variety and fun to their students. I love the interdisciplinary nature of the event,” Kane adds. Strutt wrote that there is a literary and performing arts component to the pastime of quintain, too. For example, Shakespeare refers to it in As You Like It (I, ii), when Orlando says, “My better parts are all thrown down/And that which here stands up/Is but a quintain, a mere lifeless block.” During the joust, Kane playsWe Will Rock You, a Queen song used in the 2001 Heath Ledger film, A Knight’s Tale, to inspire the competitors and to add excitement.

This is not the first time Kane has used her historical research in practice. While serving as Director of Dance for the Trumansburg Conservatory of Fine Arts, she successfully created and taught a class called Rough and Tumble to encourage young boys to become part of the program. It was based on German gymnastics, parkour or freerunning, and stage combat. With a background as an advanced actor/combatant in the Society of American Fight Directors, she has taught armed and unarmed stage combat to Cortland performing arts majors as well as members of the varsity football and gymnastics teams.

Jousts were the first instance in sports history in which scorecards were used, and the class scorekeeper eventually announces the champion of the day. With typical chivalry, Sir Ethan Irons (’21) invites the entire Gold team to pose for the photo with their shortbread cookie prizes (provided in lieu of a feast). Kane will later print and bring in copies of the photo for each member of the team as a memento. “Transformational Education is part of life at Cortland under our Campus Priorities,” Kane says, “and I love it when we can integrate different aspects of learning into memorable events!” Judging from the expressions on their faces in the photo, her students agree.

Date posted: February 21, 2020

by Dan Harms, Chapter Vice President for Academics –

The Cortland refrain on our Discretionary Salary Increase money (DSI) process is that it rewards “merit.” Does it?

To start out, let’s say that the campus should be recognized for allowing employees to have a voice in the process of deciding how contractual DSI money is handed out, both in the application phase and giving them an appeals process. This is not something they’re required to do.

But is it about merit?

We’ve just received the data from the DSI allocation from the last round which ended in December. It begs for interpretation from someone who has actual knowledge of statistics, but what I can see troubles me.

Based on my interpretation of the data, the campus gave money to over three hundred DSI recipients – yet only about sixteen of those were part-time employees. Even with some caution as to these numbers, I can nonetheless ask the administration:

Some might say, “We can’t give money to people who don’t apply.” First, be aware that the campus chooses not to report the number of applicants, just the number of awards, so it’s not clear whether part timers are applying or not. Second – if part-time employees aren’t applying, isn’t this an indication of a problem with the process? Third, we have used other processes in the past. Fourth – see below.

Remember, the total of all full-time and part-time salaries determines the amount of money the campus receives for DSI. We should avoid the process becoming one in which one group of faculty receives the overwhelming number of awards.

Second, we should talk about Information Resources, my own unit, which has many people doing hard, highly-skilled work crucial to the campus’ success. In addition, while the administration has made some effort to deal with salary compression in other units, IR has not been one of them. Thus, IR has many people eager for some reward for their efforts after many years, and many employees applied for DSI this round.

The first level of application review in IR went smoothly. When it reached the second level, however, management chose to avoid making any recommendations – something that the college has never done, to my knowledge. They left that call up to the third level – after the appeals process had ended. There, the decision was made to slash the ratings of many of the applicants, sometimes dropping them two tiers. Speaking for myself, my recommendation dropped from “Highly Recommended” to “Not Recommended,” and from talking with my colleagues, many others were equally dismayed with the results. The campus did grant another appeal period – for those who felt comfortable enough to write Erik – but the damage was done. Many people who had expected something for their efforts were deeply disappointed. Further, not a single part-time applicant from IR – and we did have them – received any DSI.

It’s true that the campus has only so much money to go around, but it does decide on how it allocates it in the process and the amounts of the awards at each tier. Thus, my second question:

2. How much should a “merit-based” rating of our performance depend on how many people in the unit also apply?

At this time, the next DSI process memos have already been mailed out. We’ll see how this round goes – but I’ve seen no indication anything will change in this next round.

Date posted: February 12, 2020

by Jaclyn Pittsley, President and Daniel Harms, VP for Academics –

SUNY Cortland Chapter of UUP’s bylaws are in need of amendment and revision! Our chapter bylaws govern our campus structure and they describe the functions of our local campus organization. The chapter bylaws have not been amended in many years and are seriously out of date.

The UUP bylaws committee, including Daniel Harms, Joe Westbrook, and myself, with a great deal of assistance from Jen Drake and David Ritchie, has been working for several years to amend the bylaws to reflect changes in the UUP Constitution and changes in the Chapter. I offer my thanks for their hard work.

These changes have to occur in order for our union to remain at the forefront of advocacy in these trying times of anti-union sentiment. Our bylaws as amended will now reflect important changes in categories of membership, counting of delegates, and continuing membership, in addition to changes to language and offices.

Please take a look at the highlights of these amendments listed below, and please make it a point to Attend Union Matters on April 1, 2020 in Corey Union Function Room and Vote on the bylaws. All members’ voices need to be heard, and all votes counted.

We need everyone’s help to keep our union functional and prominent in the fight to maintain and improve our terms and conditions of employment.

UUP Bylaws Highlights of Amendments – February 2020

Bylaws Notes

Bylaws brought in line with UUP Constitution and directives from statewide

Names of committees and officers changed

Increasing good governance

Article III, Membership, Section 2 – Categories of Membership

Confirms categories for Contingent Academic and Professional Members.

Section 3 – Classes of Membership

Adds Contingent and

Continuing Membership as categories

States the duration of Contingent Membership as being year-long

Establishes that dues payment is necessary for membership

States the rights of members for attending meetings and participating in

elections

Article IV, Section 3 – Meetings

Changes necessary quorum for a meeting to be 5% of the Chapter membership (just to make it easier to convene a meeting)

Article V, Section 1 – Chapter Officers

Vice President for Contingents becomes Officer for Contingents

Added Officer for Retirees, Membership Development Officer; removed Part-Time Concerns Representative as redundant

Section 2 – Selection and Term of Office

Establishes that Membership Development Officer and Grievance Officer are nominated by the incoming Chapter President for a two-year term

Establishes that the Executive Board may appoint an officer or hold a special election if no nominee is available or write-in votes don’t reach the threshold;

In case of a vacancy between the chapter elections and June 1, allows the incoming Chapter President to appoint an interim officer until the Executive Board meets.

Establishes presidential succession rules for officers

Section 3 – Duties

Allows the president to conduct Labor/Management meetings, sign checks if the treasurer is unavailable, supervise office staff, and appoint a Parliamentarian

Affirms that the Vice Presidents and Officer for Contingents are delegates

States that the treasurer should keep chapter monies in a bank account, and submit audit packets in a timely manner

Establishes duties for the Officer for Retirees, Membership Development Officer, and Outreach Chairperson

Article VI, Executive Board; Section 1 – Members

Changes the makeup of the executive board [?]

Section 2 – Duties

Confirms the Executive Board’s role in approving committee appointments and carrying out statewide policy

Lowers the number of appointed offices for which the Executive Board can define duties

Establishes that Executive Board members serve as delegates to the Delegate Assembly

Section 3 – Minutes

Stipulates that minutes shared with Chapter members should be approved beforehand

Article VII – Other Chapter Officers

Eliminates the alternate delegate, in favor of regular delegates

Establishes that the Executive Board may create only chapter officers who are non-voting, and may define the duties thereof

Article VII – Committees

Section 1 – Standing Committees

Clarifies which officers may attend Labor Management meetings, with the stipulation that others may be brought at the chapter president’s invitation

Provides membership for Part-Time Labor Management meetings, as well as the Contingent Employment Committee, the Affirmative Action Committee, Grievance Committee, Membership Committee, Outreach Committee, and Environmental Health and Safety Committee, if the chapter chooses to appoint them

Article IX – Chapter Elections

Section 1 – Chapter Election Dates

Chapter elections to be held in odd-numbered years, not “every two years”

Section 2 – Chapter Elections

Confirms that the Vice Presidents should be elected from their membership

Clarifies which positions are elected and which appointed

Grants the Executive Board the ability to appoint vacant positions for which no nominee or willing write-in candidate exists

Article X – Recall

Establishes a procedure to remove an officer for neglect, misuse of Chapter funds, or intentional misrepresentation, ending with a chapter vote for removal.

Article XI – Parliamentary Authority

Establishes that Robert’s Rules of Order applies to meetings in cases where the UUP Constitution or Chapter Bylaws are silent

Article XII – Governance

Section 1 – Construction and Severability

States that the UUP Constitution changes will automatically amend the Bylaws when these conflict

Provides that a copy of revised bylaws should be kept in the chapter office for examination

Section 2 – Amendment

Bylaws may be created by a petition sent to the executive board

A vote on an amendment may be held at a Chapter Meeting and take effect immediately

Date posted: February 4, 2020

by Karla Alwes, Distinguished Teaching Professor, English Department –

Because there are so many protests to be made against the Trump administration, we may be forgiven not to have noticed a current trend in education funding that needs to be included in the growing slate of protests. Since the shockingly farcical idea to decimate funding for Special Olympics in 2018, proposed by either Education Secretary Betsy Devos or US President Donald Trump, neither of whom would own up to suggesting it, DeVos and Trump have gotten together to conspire against education altogether.

While teachers nationwide are striking for better working conditions, the cuts to federal education budgets continue to grow. According to the Center for American Progress, New York’s cut in funds for state grants in 2020 is $148,594,992. Nationally the budget cuts for state grants in education for all states have grown to $2,055,830,000. (In 2019, total cuts in education funding, the Center for American Progress advises, reached $8.5 billion [americanprogress.org/issues/education]).

Our students who aspire to teach, and who have always been told that to be a teacher is a noble and worthy profession, may be shocked to discover otherwise. Or, they may already understand the divide that exists, the one between the idea of public education for all, that the federal Secretary of the Education Department personally and publicly eschews for that other idea—private institutions of education that don’t need the government’s money because they have their own, a “sordid boon,” as the poet William Wordsworth may call it, because so much of it comes from the continuous tax cuts to the wealthy, paid for by the others.

For decades, public school teachers have had to pay for their own pencils, crayons, glue, gold stars, and whatever other paraphernalia help make up the classroom that invites children and students beyond childhood to experience the joys of learning. It seems that now those same teachers will have to pay for their own dignity as a public teacher, as we all struggle to restore what has become, through the back channels of Washington, the battered nobility and worth of our profession.

Date posted: December 6, 2019

In my role as Chapter President, during the last six months, I have served as a confidant to those who’ve been subject to treatment by others that requires me to remind folks of our commitment to excellence, solidarity, and mindfulness.

SUNY Cortland is one of the finest institutions in public higher education, and it pains me to hear that folks are requiring their colleagues to do things that are not a part of their professional obligation, such as being told to fetch mail, pour coffee, or run personal errands.

UUP is an inclusive environment where, as Dr. Seuss puts it, “Every Who down in Who-Ville, the tall and the small….” are represented and deserving of fair and equal treatment. We all deserve the right to work without fear of being asked to do things that are outside our professional obligations, especially by our fellow members and supervisors. No one wants his or her work degraded by unnecessary requests for “favors” of a servile nature, and no one wants his or her commitment questioned for pointing out these unfair and even outrageous requests.

All UUP members work with special protections and a special imperative: a voice with which they must expose injustice that occurs in their work environments. No one should be considered “too soft” to work at SUNY Cortland, especially when they’re brave enough to stand up for themselves and others. Such an accusation has no place in an institution such as ours: it smacks of hazing and makes the mind reel with its implications, especially considering our country’s profound support and progressive participation in recent #MeToo Movements. We all deserve the right to work without fear of punishment or reprisal for declaring, “NO, this is not what I have to do to get where I want to be.”

I say this not to chastise any fellow member who has made such a request of a fellow employee or of a supervisee. We have all, including me, asked at one time or another for a small favor of a colleague that is gladly done. However, we should be mindful of inclusivity and the dignity our colleagues deserve in performing their work for this institution. We have all made requests that may seem minor or trivial, and we may have made these requests many times without thinking of how the request makes the other person feel. I ask us now to think about it, to empathize with our fellow employees, to consider times we’ve imposed unfairly upon one another.

UUP is a muscle of change. We work for change in our terms and conditions of employment. We demand change in our environment. We progress beyond acceding to the ways that things have always been done. We are not a group to sit idly by while others endure ill treatment, lack of care, or retaliation for speaking out. We reach beyond the old and champion the new.

UUP members have specific obligations to themselves and our colleagues in the workplace. I hope, and I’m sure my fellow members would find it reasonable, that my colleagues will be able to view the experience of working with me in a positive way, filled with useful interactions, even on occasions when we may disagree. I want to continue to work toward this goal in the coming year, and I hope we can all do the same. Every human being on this campus – UUP Members or Non-Members, CSEA, PEF, CWA, student, administrator, guest, or visitor, Full-Time or Part-Time, Permanent or Temporary Appointee, new hire or long-serving senior member, supervisor or supervisee – deserves the respect of all colleagues and must be able to perform their obligation with dignity.

Date posted: December 4, 2019

Contributed by Denise D. Knight, Distinguished Teaching Professor Emerita, English Department, and Noralyn Masselink, Professor, English Department –

As part of The Cortland Cause’s Spotlight on Course Teacher Evaluations

Years ago, when our careers were in their infancy, a colleague in our department confided that he never assigned a paper grade lower than a B. A kind-hearted and well-meaning soul, to be sure, he told us that anything less than a B had the potential to damage a student’s self-esteem. To our protest that inflating grades had, among other things, the effect of exaggerating a student’s perception of her skills, he responded that that was a good thing, because it would bolster her self-confidence. We eventually agreed to disagree.

The issue of grade inflation has the potential to cause discord in even the most collegial quarters. Inflated grades are a common occurrence on college campuses, for reasons ranging from our colleague’s philosophy that artificially promoting positive self-esteem does more good than harm to the position that it is much easier to assign a high grade than to defend a low one. Concerns about students retaliating against low grades by producing damaging course teacher evaluations is another reason faculty exaggerate grades. An article in Forbes by Tom Lindsay in March 2019 paints a particularly grim picture of the trends in grade inflation: “Virtually all new college graduates sport nothing but A’s and B’s on their transcripts. For the same reason, grade inflation also hinders the ability of graduate school admissions boards to differentiate meaningfully among student transcripts.” Likewise, Duke University professor Stuart Rojstaczer, on his website, www.gradeinflation.com, which features extensive research on the topic, documents the trend with a series of graphs and charts. Rojstaczer’s study also confirms that “A is the most popular grade in most departments in most every college and university.” On some campuses, there is subtle pressure, in a market that competes for students, to raise the institution’s profile—and hence its appeal—by inflating grades. As Jonathan Dresner observes, “Student retention and graduation rates are used as measures of institutional effectiveness, which mitigates against failing (or even discouraging) even the most unprepared students.” The problem pervades all levels of higher education, from community colleges to elite universities. In an illuminating article that appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2001, Harvard professor Harvey C. Mansfield exposed the problem of grade inflation at his Ivy League institution by noting that fully half of Harvard’s students graduate with “outlandishly high grades” of A or A-. “Grade inflation has resulted from the emphasis in American education on the notion of self-esteem,” Mansfield writes. “According to that therapeutic notion, the purpose of education is to make students feel capable and empowered. So to grade them . . . strictly, is [viewed as] cruel and dehumanizing.” But however well-intended, we would argue that grade inflation is never justifiable. While much of the literature addressing this topic examines the impact on the professor and on the institution, little of it deals directly with the effect of grade inflation on the student. Not only are there ethical concerns, certainly, but another critical factor should be taken seriously: when we create a culture in which we overstate the worth of a student’s performance by assigning a grade that does not honestly reflect ability, we are not serving that student responsibly. On the contrary, we may very well be setting the stage for future failure.

Most of us who assign honest grades have heard the familiar complaint levied by frustrated and oftentimes angry students: “But I get As on all my other papers!” Our response is not one that they want to hear. We tell them that if their essay reflects the quality of writing that they are submitting in other classes, their professors are committing a profound disservice by awarding a grade of A. The student will sometimes return with an A paper in hand from another course to “prove” to us that our standards are impossibly high. When we inevitably point out serious weaknesses in their essay, from incomplete sentences to errors in agreement and arguments made without the benefit of textual evidence, the student typically becomes more adamant in her assertion that the problem is ours. After receiving a course grade of B-, one student e-mailed the following query: “I am writing you in concern for [sic] my overall grade in the course. . . . Does [the B-] mean that I did that bad on the final? I really believe I did well on the final. Did something else take into effect [sic]? . . . I did not miss more than the alotted [sic] classes. I have enough class participation. The only thing that I had that was bad was the paper. Could you please let me know what I got on the paper and anything [sic] I should know?” It was only after three more messages from the student, each one more urgent and defiant than the last, that she finally accepted the outcome as a simple question of mathematics. What is most curious, though, about the student’s inquiry is her belief that a grade of B- is somehow “bad.”

At SUNY Cortland, and at countless other institutions, an A is defined as “superior performance,” a B indicates a “good performance,” a C is awarded for “fair performance,” and a D is “minimally acceptable.” Many students, however, view a “good” grade as not good enough. Anything less than an A is often perceived by the recipient as a dismal failure. As Mansfield states, “today a B- is a slap in the face” (qtd. in Bruno). We have seen countless tears, listened to emotionally wrought pleas, and witnessed outright meltdowns when students earn a “good” grade of B. Unless professors work very hard to justify grades of C or D, there are almost always follow-up e-mail inquiries, phone calls, or office visits from dissatisfied students demanding an explanation. Many of them seem unable to fathom the fact that their performance is legitimately less than superior, or, at the very minimum, merely “good.”

A number of factors contribute to students’ perceptions that a B is “bad.” One leading cause, as Kurt Wiesenfeld notes, is that the current generation of students has “been raised on gold stars for effort and smiley faces for self-esteem” (16). Indeed, in our experience, students today often perceive grades lower than an A as a judgment of their character, rather than as a measure of their performance. Because the popular wisdom endemic in their generation has been to preserve and bolster self-esteem (criticism of any kind is viewed as destructive and unkind), many students have been coddled and rewarded for mediocre achievements. Like Wiesenfeld, Mansfield, too, condemns the present trend. “There is something inappropriate—almost sick—in the spectacle of mature adults showering young people with unbelievable praise,” he argues. Honest grades, as opposed to those that are routinely inflated, are often a wake-up call for students who spend much of the semester in a state of intellectual slumber. When it becomes apparent that not all instructors subscribe to the culture that promotes easy As, students often become reactionary. Panic, anger, and defensiveness are common responses.

A second factor influencing students’ perceptions of grades is that they view themselves as customers in a consumer culture who are, in essence, “paying” for a degree rather than earning one; as a result, there is a sense of entitlement in their demand for higher grades. “Students have developed a disgruntled-consumer approach,” Wiesenfeld notes. “If they don’t like their grade, they go to the `return’ counter to trade it in for something better.” At Cortland, this practice is encouraged by the fact that students can withdraw from a course as late as three weeks before the semester ends without many consequences. In the past, when a student withdrew, instructors could indicate whether the student was passing or failing the course. The present system, however, enables students to withdraw with no record of their course status. It has become too easy to simply erase indicators of past performance, lulling students into a false sense of security—or, worse yet, denial—about their academic abilities. With no official record establishing a history of uneven academic performance, it is easy for students to convince themselves that all is well. The sad irony, of course, is that when students bail themselves out of a course in which they are struggling (valid reasons for course withdrawal notwithstanding), they become complicit in their failure to meet a legitimate intellectual challenge. As Dresner notes, “the ideology of ‘student as consumer’ has changed the power relationships within the academy, placing satisfaction higher than intellectual growth as a measure of success.”

A third reason that students challenge fair assessments of their work stems from the simple semantic inversion that leads students to conclude that the “good” grade of B is actually “bad.” While most dictionaries offer some two dozen definitions of “good,” students apparently view the word as an antonym for “excellent,” rather than the next logical stage on a linear scale. Surely, we can apply the term to even the poorest student work and end up characterizing that student’s performance as “good.” For example, “it was ‘good’ of this student to turn in his [otherwise atrocious] work on time.” Or, “despite a disappointing result, this student at least made a ‘good’ effort.” An instructor might even find that a student’s dismal performance on a final draft is at least “‘good’ compared to the first one.” The list goes on and on. At the same time, however, since a grade of C is meant to indicate a “fair performance”—and considering that “fair” can mean anything from “moderately good,” “acceptable or satisfactory,” to “promising”—we wonder why professors who resist assigning C grades find them so destructive. If no student’s work is being judged as being “fair” or “minimally acceptable,” then why do institutions retain the possibility of assigning grades of C or D at all?

Certainly, this question has evoked a spirited debate on college campuses nationwide. In a 2005 Washington Post article that garnered much attention, Alicia C. Shepard confronted the issue head on. She acknowledged that early in her teaching career at American University, she had, on occasion, bowed to the pressure from students who challenged their grades. Students “bribed,” “pestered,” “bombarded,” “harangued,” and “harassed” her. Although she had reservations about modifying grades, she nevertheless succumbed, until a “university official,” citing unfairness, rejected a grade change, effectively ending her reputation as a softy. In our own program, students who need to retain a minimum grade point average in order to stay in the teacher education program regularly engage in such grade lobbying when they miss the cutoff by a few tenths of a point. Thus, the end of the semester regularly finds such students making the rounds from one professor’s office to the next pleading their case. The problem, however, is that students who “squeak” into programs through such back-door means generally struggle when it comes time for them to perform in their own classrooms. In other words, poor grades and a low or borderline GPA often corresponds to poor performance as a student-teacher—a correlation which comes as no surprise if the courses in which the student has done poorly are meant to equip the student for later professional performance as a teacher. In essence, then, when sympathetic professors agree to change a student’s grade, they often set the student up for an even greater struggle further down their academic path, when the stakes are generally higher. Such well-meaning gestures are a recipe for future disaster.

So why do so many faculty members compromise their integrity by assigning fictitious grades? Rojstaczer, for one, is candid about his reasons for assigning a disproportionate number of As and Bs: “As are common as dirt in universities nowadays because it’s almost impossible for a professor to grade honestly. If I sprinkle my classroom with the Cs some students deserve, my class will suffer from declining enrollments in future years. In the marketplace mentality of higher education, low enrollments are taken as a sign of poor-quality instruction. I don’t have any interest in being known as a failure.” In fact, faculty are oftentimes reluctant to issue fair and honest grades because they fear retaliation from students on end-of-the-semester course teaching evaluations. This anxiety is fueled on college campuses where high teaching scores are tied to tangible monetary awards in the form of raises or discretionary salary increases. Inflated grades become the currency that buys strong evaluations. Websites like ratemyprofessors.com encourage students to rate the “average easiness” of their professors, and high “easiness” ratings typically result in strong overall scores for those professors. As a result, it’s not uncommon to see comments like the following, which were made about a professor with an overall score of 4.5 out of 5: “Not a very difficult class, and we ended up watching clips from family guy and Jackass the movie. Really easy to talk into cancelling class.” There is an implicit quid pro quo: students will provide inflated teaching scores in exchange for high grades (and, in this case, for canceled classes). In another class, where the instructor rated an overall score of 5.0 and a difficulty level of 2.0, a student wrote that the instructor “doesn’t assign much work at all, in fact most of the reading is done in class.” Several other students wrote of this instructor that his courses were “super easy” or an “easy A.” Untenured faculty may be particularly vulnerable to the pressure to secure strong CTEs, since continued employment is so often contingent upon satisfactory teaching. “Unfair” or “hard” grading is a commonly voiced complaint on course evaluations. One student wrote on their CTE that the instructor “grades as though we were at Harvard.” Such a statement suggests that because admission standards at a public college are lower than those at a private or Ivy League institution, the grading standards should be adjusted downward as well. But we believe that regardless of the insignia on one’s diploma, all students should be held to a rigorous standard. Offering them anything less is simply irresponsible.

Yielding to student and even institutional pressure, however, is only one factor behind exaggerated grades. Some members of the profession may, perhaps unwittingly, be plagued by nagging doubts about the quality of their teaching, which, in turn, elicits the belief that if their students underperform, they have themselves somehow failed. The ensuing guilt (“I must be doing something wrong”) can cause instructors to overcompensate for their inadequacies—either perceived or real—by elevating grades. But when instructors do impose honest low grades, they can still be riddled by guilt, particularly when the student pleads for mercy, because a low grade will mean that they won’t be qualified to continue in a program, to apply for a scholarship, or to graduate on time. In his 1996 short story, “A Gentleman’s C,” American author Padgett Powell examines the devastating consequences of assigning an honest grade. The story focuses on a college English professor who gives his 62-year-old father, a student in his course, “a hard, honest low C.” When the grade prevents his father from fulfilling his long-held dream to earn a college diploma, he suffers a fatal heart attack, causing the narrator to be haunted by guilt.

While honest grades don’t usually result in the degree of drama depicted in Powell’s story, the repercussions of routinely assigning high grades for inferior work are, nevertheless, far-reaching. As reported in Ken Bain’s recent study What the Best College Teachers Do, several studies have demonstrated that when students are given extrinsic rewards like good grades, both their motivation to do well and their intrinsic interest in the subject matter actually decrease if the reinforcement of good grades is removed (32). Compounding this problem is perhaps the more serious consequence that students learn to get by without making much effort. If they can whip out a paper in the hours before a final draft is due and know that they will be generously rewarded regardless of quality, their motivation for achieving genuine excellence is compromised. Why labor over a paper for weeks if winging it in the eleventh hour will yield the same results? The impetus to improve one’s analytical, research, and writing skills will be diminished or altogether eliminated.

In fact, we have found this scenario to be true even when students are given the chance to revise their work. It is not unusual for students to submit for initial feedback what they characterize as a “rough draft,” work that often resembles little more than brainstorming notes. Despite our warning that such drafts will require serious revision, students quite frequently engage instead in a superficial cleanup of the essay. They then express bewilderment as to why their “revised” draft has earned a grade of D. “But this draft is so much better than my first!” they cry, with little understanding that the word “draft” implies a preliminary sketch, rather than a finished product. Certainly, responding to drafts, and allowing students to revise, affords them an opportunity to learn from their mistakes, but in an environment where students have been able to artificially excel, demanding additional work is often viewed as a punishment rather than an opportunity. When we insist that extensive revisions need to be made, students often balk. It’s not unusual for them to resist—or even to challenge—the notion that it may require considerable work for their performance to be good, let alone superior. Even with additional efforts on the part of the student, however, we don’t make promises about grades that we simply can’t keep. There are times when we have evaluated third and even fourth drafts that don’t meet the standard of “fair” work; at the same time, however, we have seen poorly conceived preliminary drafts undergo the kind of extreme makeover that has resulted in a bona fide grade of “superior.” Those students who rise to the occasion seem to understand that until their work is truly “superior” or “good,” it will not be awarded a grade of A or even B no matter how many revisions they have undertaken. In other words, we do not award effort unless that effort results in significantly improved work. Once students accept those terms, they can meet the challenge and adopt the mantra of all good educators that “every student is capable of learning,” if we enable them to.

Sometimes, in order to illustrate our point that “effort” alone can’t always be rewarded, we offer analogies. We ask students whether they would seek treatment from a doctor who had tried “really hard” to get through medical school, who put endless hours into his work, but who couldn’t pass his final exams. Or similarly, we ask how many students would be willing to fly in a plane piloted by someone who had logged hundreds of hours in the cockpit, but who was unable to pass his licensing test. Having students think about the expectations they have for working professionals—and the possible repercussions of falling short—gives them a better sense of how we view their performance in our classes.

Another consideration is that rewarding substandard work with inflated grades is blatantly unfair to those students who do labor over their essays and who push themselves to achieve excellence. One of our students was incensed when nearly all of her classmates received final grades of A despite the fact that many of them boasted publicly about how little work they had done for the course. As she put it, “It’s not fair that I read every page assigned and do all the work, and those who read only part of the work and fake their way through assignments end up with the same grade.” Not fair, indeed. Such scenarios make getting an education seem more like an exercise in seeing how little one can do than an effort to learn anything of value. And since the students are aware of this culture on campus, one must wonder about the degree of respect they hold for either the professor or for their education in general. As Mansfield argues, “professors who give easy grades gain just a fleeting popularity, salted with disdain. In later life, students will forget those professors; they will remember the ones who posed a challenge.”

In fact, students who are falsely conditioned to believe that they are producing A work will also have a harder time facing the inevitable disappointment when they are denied a job or admission to graduate school. Although some administrators, including Ronald Ehrenberg, Director of Cornell’s Higher Education Research Institute, believe that the quality of today’s students is higher than in the past, extant data doesn’t support that conclusion (Bruno). On the contrary, Rojstaczer’s research suggests that “There is no evidence that students have improved in quality nationwide since the mid-1980s” (gradeinflation.com). As a result, those students who have been awarded fictitious grades typically have inflated expectations and distorted judgments about their ability to find and secure employment. Students who have been accustomed to sailing through a course, regardless of the quality of their performance, may be overly confident about their candidacy. Prospective employers and graduate schools, however, who recognize that grade inflation is rampant, may ignore grades in favor of entrance exams, or, those who do they review letters of application are likely to be put off by cover letters that are poorly written. What students may not realize is that they will often be competing with hundreds of applicants and that employers often make the first cuts from the applicant pool based purely on the impression that applicants make in cover letters or resumes.

A handful of institutions are finally yielding to the pressure to address the problem of grade inflation. In 2004, Princeton University, by a vote of 156 to 84, passed a grade deflation policy that limits “A-range grades to 35 percent in undergraduate courses.” Dean of the College Nancy Malkiel emphasizes the benefits of “grading in a more discriminating fashion.” One of the advantages, she notes, is that “faculty members are able to give clearer signals about whether a student’s work is inadequate, ordinary, good or excellent” (Bruno). The trend toward changing the culture that accepts grade inflation, however, is discouragingly slow.

Those professors who rubberstamp student papers with As and Bs, because they are easygoing, indifferent, desperate to attain strong CTEs, or simply overwhelmed by mountains of essays, make life much harder for their colleagues who do insist on high-quality performance. But the biggest detriment to students who are subjected to a culture in which an “easy A” is a given is that it denies them the opportunity to strengthen their skills, to grow intellectually, and to experience the enormous sense of accomplishment that comes from genuine hard work. Assigning honest grades consistently is the first step in preserving not only personal and institutional integrity, but also in promoting responsible teaching. We owe our students that much.

Date posted:

Contributed by Sean Dunn, graduate assistant for Recreation, Park and Leisure Studies –

A student coalition calling for a ban on the sale of single-use plastic water bottles on Cortland’s campus has gathered more than 650 signatures over the course of the fall semester. Under the leadership of Cortland graduate students Olivia Terry and Sean Dunn, the Clean Water Coalition (CWC) has spotlighted the environmental and social problems associated with the bottled water industry through informative tabling exhibits and educational events. By collaborating with a number of environmental organizations and academic departments on campus, Terry and Dunn’s cause has recognized a fundamental incompatibility between the sale of bottled water and the college’s sustainability goals.

An independently organized student group, the CWC formed last spring following the Sociology/ Anthropology department’s screening of Tapped, an environmental documentary detailing the noxious health effects and social injustices associated with the bottled water industry. Channeling the momentum of a productive spring semester, the CWC hit the ground running this fall, acquiring the signatures of more than 60 student clubs at the SGA’s annual club fair in early September. Since then, the CWC has held a number of educational events, including a free reusable water bottle giveaway and a Sandwich Seminar. With the support of the SUNY Cortland Green Reps, the Cortland NYPIRG office, and students in Dr. Gigi Peterson’s pre-student teaching seminar, the CWC’s tabling events have played a crucial role in spreading awareness of the issue of bottled water on Cortland’s campus.

The movement comes at a time of ambitious environmental activism infiltrating the nation’s collegiate system. Flying the banner of the Food and Water Watch’s Take Back the Tap campaign, more than 70 colleges and universities have implemented partial or full bans on the sale of single-use plastic water bottles since 2005. A student-led climate change protest disrupted a football game between Harvard and Yale for nearly an hour on Saturday, while activists in California successfully lobbied for the UC system to divest from fossil fuels last month. As the effects of global climate change become jarringly embedded in our day-to-day reality, activist groups on college campuses are mounting a defense against environmental destruction.

Riding the high of a successful fall campaign, the CWC is looking to solidify the public right to clean, free drinking water in the spring semester. With the Auxiliary Services Corporation’s (ASC) contract with Coca-Cola expiring in July of 2020, the administration has an opportunity to re-write the contract and eliminate the sale of bottled water on Cortland’s campus. The ban would fall in line with the college’s prominent sustainability initiatives, which include the construction of a LEED Platinum residence hall, the development of a large-scale solar panel field, and the signing of the American College and University Climate Commitment. As the groundswell of collegiate environmentalism continues to demand action from administrative officials, the elimination of bottled water may be Cortland’s next step towards ensuring a sustainable future.