|

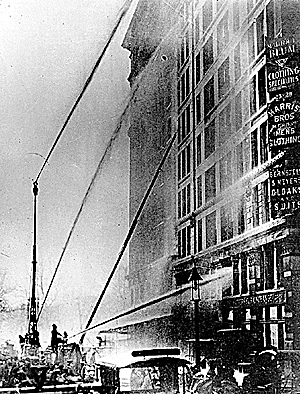

Morris “Whitey” Passoff couldn’t believe his eyes. The 15-year-old copy boy for the New York World watched in horror as Triangle Shirtwaist Co. employees, most of them young women and teenage girls, climbed out windows and stood in groups of twos and threes on the thin ledges outside the upper floors of the blazing Asch Building. Then they jumped. Some held hands as they leaped, their long dresses flapping and tresses whipped by the wind before thudding the pavement below. They fell eight, nine, ten stories, choosing instant death over dying in the inferno that killed 146 workers—many of them female Jewish and Italian immigrants—on a sunny Saturday afternoon, March 25, 1911. “When my father got there, the fire was going full blast. He couldn’t turn away. Those kids jumping out the windows, it was a memory he never forgot,” said UUP retiree member Judy Wishnia, Passoff’s daughter, whose dad told her the story when she was a child. “He said it was like watching angels dropping.” Unions have never forgotten these fallen workers, whose deaths led to sweeping workplace reforms and a huge boost for the fledgling labor movement. In March, labor across America will pay tribute as they mark the 100th anniversary of the Triangle fire. A March 25 memorial will be held at the Asch building in Manhattan by Workers United, which includes former members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), which ceased after a 1995 merger. The ILGWU, a key player in labor history in the early 20th century, counted a number of Triangle employees as members. In Albany, UUP, NYSUT, and other unions will take part in a Triangle memorial at the New York State Museum. The names of the deceased will be read at both events. FIRE! No one knows how the Triangle factory caught fire; the fire marshal blamed it on a lit cigarette tossed in a scrap fabric bin under a cutter’s table. The horror began around closing time, at 4:45 p.m. That’s when worker Eva Harris screamed to factory manager Samuel Bernstein and pointed to smoke in a corner of the eighth floor. Bernstein tried to turn a hose on the flames, but it didn’t work. Workers doused the fire with buckets of water, but the blaze was already raging. An eighth floor bookkeeper who phoned 10th floor employees about the fire couldn’t reach the ninth floor, which lacked fire alarms. One of the two exits on that floor was bolted shut; management locked workers in so they wouldn’t steal. Dozens of employees were able to scramble out the second exit, which led to the roof. But fire blocked it minutes later. Terrified workers jammed into two freight elevators, which only held 12 people at a time. The elevator operators saved dozens of lives before the fire—and the bodies of workers who jumped down the shafts in a desperate attempt to escape—ground them to a halt. The flimsy fire escape twisted and snapped under the fire’s heat and the crush of workers clinging to it, sending victims spiraling to a concrete courtyard more than 100 feet below. The fire department’s ladder trucks were useless; they only reached the sixth floor. It was over in 30 minutes, but by then, nearly 150 workers had perished. Of those, 54 died by jumping; their bodies lay in piles on the street as firefighters worked to extinguish the blaze. Ironically, the building itself was fireproof. “It was for that generation as traumatic I suppose as the World Trade Center disaster was for us,” David Von Drehle, author of “Triangle: The Fire that Changed America,” in a 2003 National Public Radio interview. “It was a beautiful spring afternoon in the middle of bustling Manhattan and hundreds, then thousands, of people gathered to watch this fire burn through this factory and see these jumping and falling bodies.” JOIN A UNION! The Triangle blaze sparked intense interest in unions, which saw a sudden upsurge in membership after the tragedy; workers flocked to join the ILGWU and its fight for worker safety reforms and better conditions for factory laborers. And join they did. The ILGWU’s ranks swelled from 2,200 in 1904 to 58,400 by 1912, according to The Historical Dictionary of Organized Labor by J.C. Docherty. The Triangle fire and large-scale strikes like the Uprising of 20,000 in 1909-10 were major catalysts. More than 120,000 marched in a funeral procession for the fire victims in a citywide day of mourning called by the ILGWU. “The fire certainly called attention to what unions had been fighting for and was vindication of what unions were talking about,” said UUPer Ivan Steen, a UAlbany history professor. “After this event, the public saw that the unions were right, there was a problem.” “The garment industry was an immigrant industry by and large and most people didn’t understand what unions did,” said Edgar Romney, secretary-treasurer for Workers United and a longtime ILGWU member. “The fire propelled unions’ growth as the public realized there was a need for safety measures for these workers.” UNSAFE WORKPLACE As workers joined unions in droves, an outraged public demanded action to improve unsafe workplace conditions. In June, 1911, the Factory Investigating Commission was created; union leader Samuel Gompers was a commissioner and Frances Perkins—who became U.S. Secretary of Labor—also served. The committee spurred more than 30 new workplace safety laws, including the installation of automatic sprinklers, lighted exit signs, fire walls, fire extinguishers and fire alarms in factories. Also ordered: building inspections, and proper lighting, ventilation and cleanliness in factories. “There were other workplace tragedies, but the Triangle fire led to major health and safety reforms,” said Paul Cole, executive director of the Albany-based American Labor Studies Center. Those reforms were a pipe dream for workers in sweatshops like the Triangle Shirtwaist Co. where employees toiled 12 hours a day, six days a week and were paid between $3 and $20 weekly, depending on their expertise and experience. “The Triangle Shirtwaist fire stands out because of the innocence of the people who were killed, they were mostly female victims, and employer disregard led to their deaths,” said UUPer David Cingranelli, a political science professor at Binghamton University. “Most workplace atrocities happened out of view, but this happened in the middle of a big city in front of thousands.” Perkins was one of those onlookers; the Triangle fire fueled her strong support for workers’ rights. As labor secretary, Perkins wrote New Deal legislation and was instrumental in bringing about landmark worker reforms such as the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Social Security Act in the 1930s. SAFETY FIRST While the Triangle fire sparked New York’s upgraded safety standards, it took decades for the rest of the nation to catch up. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Act—which had firm union backing— wasn’t enacted until 1970. Labor has been at the fore of workers’ rights, and those gains may not have occurred without labor’s push. “If you don’t have a union, it’s hard to insist on safety in your workplace,” Cingranelli said. And history repeats itself, like it did in December 2010, when 26 workers died and more than 100 were injured in a blaze on the ninth floor of a Bangladesh garment factory. Many of the workers jumped to their deaths; the exits to that factory were locked by management, to keep workers from stealing. “Things haven’t changed that much,” said Wishnia. “If it wasn’t for unions, there would be no worker safety at all.” — Michael Lisi

|

Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/uuphos5/public_html/voicearchive/wp-includes/class-wp-comment-query.php on line 405