|

Every year, SUNY and numerous academic and professional organizations honor hundreds of UUPers for top accomplishments in their disciplines, on campus and in their communities. The Voice is pleased to recognize four of these members here. • Laura Kaminsky, a professor of music at Purchase State College and a world-renowned composer, recently took part in a two-week fellowship in Russia designed to help promote Russian culture in the U.S. The fellowship was awarded by the Likhachev Foundation. • Roxana Pisiak, a professor of humanities at Morrisville State College, recently earned a Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, which recognizes professors who show scholarship and growth and a commitment to students. • Patrick Regan, a professor of political science at Binghamton University, has written a new book, Sixteen Million One: Understanding Civil War (Paradigm, 2009). Regan draws from a decade of research on civil conflicts to explore the conditions that would drive individuals to take on the life of a rebel. • Anjali Sharma, an assistant professor of medicine at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, has been awarded a three-year $300,000 grant by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to study bone loss among adults with or at risk for HIV. She is director of Downstate’s Adult Inpatient HIV?Services and medical director of the Buprenorphine Clinic for the STAR?Health Center. — Karen L. Mattison |

Category Archives: Downstate HSC

UUP honors chapter office manager with smoking cessation program

|

UUP is paying tribute to one of its fallen sisters with a new Smoking Cessation Program, unveiled by UUP President Phillip Smith last month at Brooklyn HSC.

The program honors Barbara “Bobbie” Harrison, left, the chapter office manager at Brooklyn HSC who died May 23 as a result of burns sustained in a fire started by a cigarette ember. She was the office manager at the Brooklyn HSC chapter for 12 years.

“We are all devastated by her loss,” said UUP Treasurer Rowena Blackman-Stroud, Brooklyn HSC chapter president. “Helping others to stop smoking would be a fitting tribute to her memory.”

The “Take One Step for Bobbie” campaign officially kicks off Sept. 9, with a memorial service and “Quit Smoking Now” program that includes a chapter-sponsored contest to give up smoking for a week and the opportunity to enroll in the campus’s smoking cessation study.

In 2009, UUP will expand the campaign to include fire prevention and safety, and an educational component.

For more information on the program, contact Blackman-Stroud at rblackma@uupmail.org or Isabel Rodriguez at isabel.rodriguez@downstate.edu.

— Karen L. Mattison

Letters: Colleagues defend Damadian as inventor of MRI technology

To the Editor:

In the April 2008 issue of The Voice, professor Arnold Wishnia appears surprisingly misinformed. MRI began with the 1971 science paper in which Raymond Damadian, an MD-biophysicist at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, discovered proton T1 and T2 relaxation differences among different normal tissues and between normal and cancerous tissues, and proposed external NMR scanning of live humans based upon these differences.

In a 1972 patent, Damadian described a video-like field-focusing method to scan cross-sections of the human body. This idea was not a dead end nor abandoned. In 1976, Damadian published a cross-sectional image of a mouse with a lung tumor on the front cover of Science. The next year, Damadian published the first whole-body magnetic resonance images of chest and abdomen in normal humans and patients with cancers, using a human-sized superconducting magnet built in his lab at Downstate.

Inspired by Damadian’s science paper, Paul Lauterbur reported the first gradient imaging technique in his 1973 Nature paper (not 1969, as stated by Wishnia). Lauterbur reconstructed two-dimensional images using magnetic field gradients in different directions, imaging two capillary tubes in water, later a clam. Wishnia seems unaware, however, that the “fundamental breakthrough” of getting distance information using magnetic field gradients was independently made 20 years before by Gabillard, in France, and Carr and Purcell (1952 Physics Nobel) at Harvard. They reported that NMR field gradients could generate linear density maps, essential to Lauterbur’s reconstruction technique.

The early imaging methods of Damadian, Lauterbur and Mansfield were all supplanted by spin-warp imaging, developed at University of Aberdeen in 1980. Spin-warp imaging combines phase-encoding with Ernst’s two-dimensional Fourier NMR concept, and with improvements remains the preeminent MRI method today.

Basic to all MRI machines are tissue proton relaxation differences that account for the precise soft-tissue detail unique to MRI. The crucial role of tissue T1 and T2 differences led the U.S. High Court of Patents and Supreme Court in 1997 to uphold Damadian’s 1972 MRI patent. The discovery and development of MRI was clearly multidisciplinary, but Wishnia — like the Nobel Committee for physiology or medicine — has ignored the fundamental biomedical discovery toward which MRI machines are directed to this day.

— Richard Macchia and Paul Dreizen, Brooklyn HSC

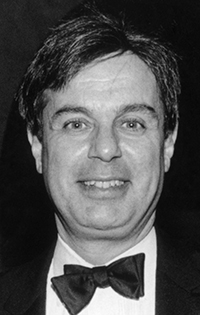

Making a case: Brooklyn HSC doctor, researcher dispute former professor’s 2003 Nobel Prize snub

|

|

The Brooklyn Health Science Center has a Nobel Prize winner in Robert Furchgott.

It almost had a second in Raymond Damadian, one of the pioneers of magnetic resonance imaging research (MRI).

Damadian, a former professor of medicine and biophysics at Brooklyn HSC, publicly proposed the concept of an MRI scanner as a means to detect cancer in 1969. In 1977, the scientist produced the world’s first MRI scan of a human with a scanner he built at the university. He holds the first patent for scanning the human body by magnetic resonance and was honored with the 1988 Medal of Technology — the country’s highest honor for technological advances — in recognition of his work.

Despite his successes and accolades, Damadian, a former UUP member, was passed over for the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

That oversight seemed outrageous to Richard Macchia, a distinguished teaching professor and chair of the Brooklyn HSC Medical School’s department of urology. Macchia, a longtime UUP member, said he was shocked when he first heard the news.

Then he became annoyed enough to write a research paper to prove that Damadian was as deserving of the

Nobel as the two men who won it: Paul Lauterbur and Sir Peter Mansfield. The paper, titled “Raymond V. Damadian, M.D.: Magnetic Resonance Imaging and the Controversy of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine,†was published in the September 2007 issue of The Journal of Urology.

“Based on my knowledge of MRI development, I thought that Dr. Damadian was a shoo-in for the award,†said Macchia. “It was bad enough for

Dr. Damadian to lose out on the award, but what really frustrated me was that Brooklyn HSC and the people of Brooklyn lost out on the distinction of having a second Nobel winner in five years.â€

The first Nobel winner Macchia was referring to was Furchgott, who served as a professor and chair of Brooklyn HSC’s department of pharmacology for 26 years and is presently a distinguished professor emeritus. Furchgott won the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of endothelium-derived relaxing factor, a mysterious chemical in the arteries’ inner linings that causes the arteries to become narrow and wide.

“We don’t have the kind of money that schools like Harvard and Cornell have for research, and when a professor overcomes those kinds of obstacles and challenges and, for reasons unjustified, is denied such a prize is beyond me,†said Macchia, a friend of Furchgott’s who attended his Nobel award ceremony in Sweden.

Laying claim to a second Nobel Prize winner would augment the school’s reputation for medical research.

Brooklyn HSC has had its share of medical breakthroughs over the years, including the development of the first heart-lung machine for open heart operations (Clarence Dennis), large-scale dialysis (Eli Friedman), and the development of kidney transplant surgery (Samuel Kountz).

Macchia recruited Brooklyn HSC archivist and UUPer Jack Termine and one of Macchia’s students, Charles Buchen, and went to work researching Damadian’s work to prove he was worthy of the Nobel honor. Since up to three people can be nominated, it was both odd and suspicious that Damadian was overlooked, Macchia said.

In the paper, Macchia and Termine state that Damadian’s omission for the award seems to be “serious and purposeful.†While the authors do not disagree with the Nobel Committee’s decision to honor Lauterbur and Mansfield, they claim that it is “inconceivable that Raymond Damadian was omitted.â€

The paper points out that in 1969, Damadian requested funding from the Health Research Center of the City of New York for a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer for “early non-destructive detection of internal malignancies.†He wrote about using NMR, the forerunner to MRI, as an external probe for detecting cancer in a 1971 research paper published in the journal Science. Damadian applied for a patent for his scanning method in 1972; it was awarded in 1974.

In 1977, Damadian built his scanner, dubbed “Indomitable,†with students Larry Minkoff and Michael Goldsmith at Brooklyn HSC. The NMR scanner produced the first MRI scan of a human; it was a scan of Minkoff’s chest. The scanner is on display in the Smithsonian Institution.

In the book The Pioneers of NMR and Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: The Story of MRI, authors James Mattson and Merrill Simon point out that Damadian’s 1971 paper contained five “landmark steps†in the development of NMR scanning, including his theory of the cell that led him to consider NMR as a cancer-detecting method.

Macchia and Termine included this research in the paper, as well as a list of awards Damadian won that confirm his status as an MRI pioneer. In 1989, Damadian was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and in 2001 he was honored with the Lemelson-MIT program’s Lifetime Achievement Award as “the man who invented the MRI scanner.â€

Damadian, who commercially produces MRI scanners through his company, FONAR Corp., successfully protected his patent rights in several lawsuits, including a 1997 decision against General Electric Co. that awarded him $128 million in damages.

“We used nothing but unbiased sources for this study,†said Macchia. “We didn’t use any data from Brooklyn HSC and we didn’t talk to Dr. Damadian. He knew nothing of this.â€

Since the Nobel Committee’s deliberations are sealed for 50 years after an award is bestowed, it will be 2053 before the world finds out why the committee passed over Damadian for the award. Not willing to leave that to chance, Macchia said he has a plan in place to ensure that Damadian’s story isn’t forgotten.

He said: “(Charles) Buchen should be alive in 50 years to hear what happened, so I have extracted a promise from him to write a follow-up article about this.â€

— Michael Lisi